by Jane

Boozhoo! Daga biindigen Anishinaabeg Oodena.

Welcome! Please come in to the Ojibwe Village.

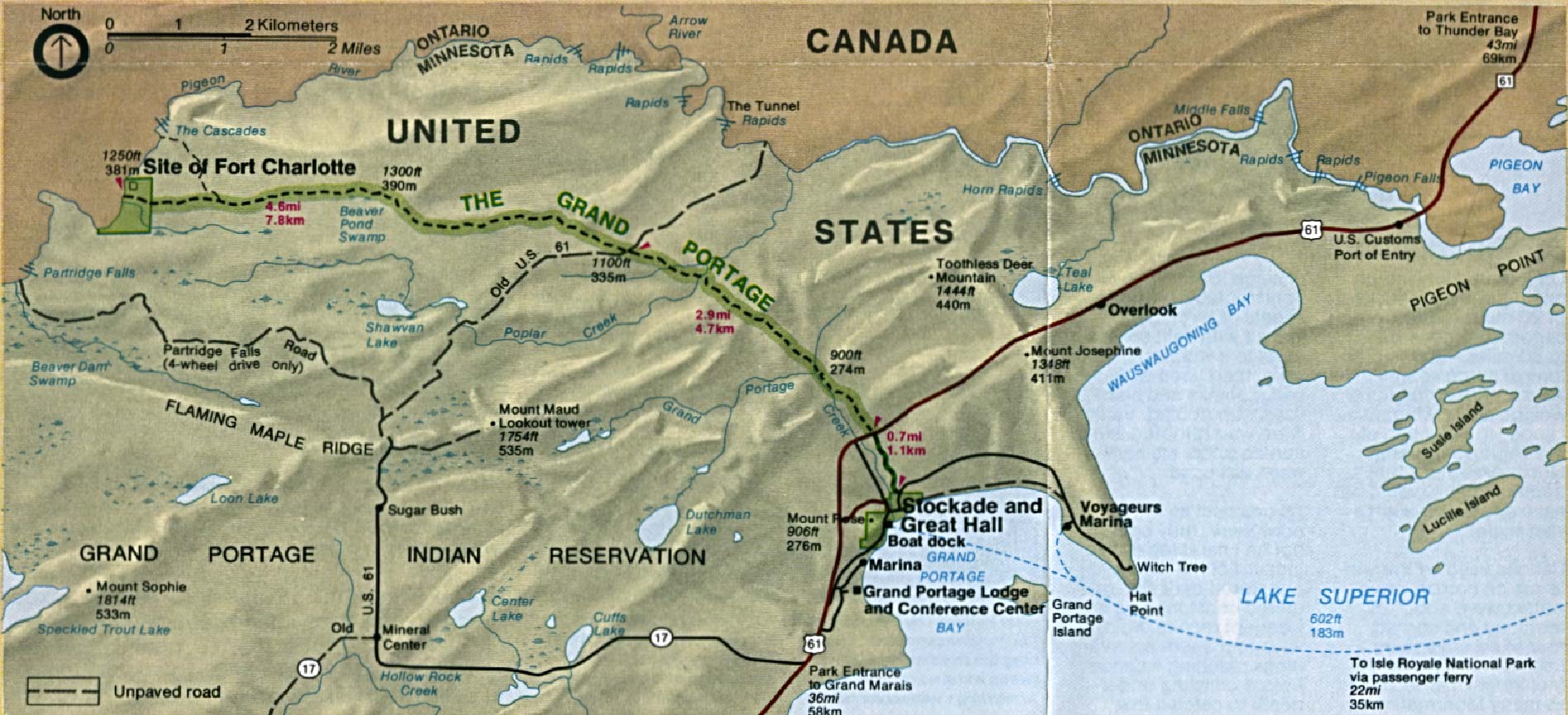

Thanks for joining us on this tour of Grand Portage National Monument, where Steve and I are volunteering this summer. (If you missed the first post of this series, in which Steve gives an overview, you can read it here.)

As you enter the historic site, you are welcomed into the Ojibwe* Village. More accurately, to a representation of a summer village, because in the 18th-century, the Ojibwe people moved with the seasons.

Seasonal Lifeways

Niibin -- Summer Summer was the time for living on the shores of Gitchi Gami, Lake Superior. Besides providing relief from the heat of summer (the lakeshore at Grand Portage is often 10 degrees cooler than our RV site just a half-mile inland), Lake Superior provided fish in abundance. Usually you will see fish drying near the fire, so that they can be stored for winter.

You'll also see a "Three Sisters" garden. What we now call "companion planting"--using plants that grow better together than apart--seems to have been universally known among Native peoples. The "sisters" are corn, beans, and squash. Beans provide nitrogen for the corn and squash; the corn provides a support for the beans; and the squash (when it thrives, which it has so far failed to do in our garden this year) crowds out weeds, shades the ground to conserve moisture, and deters critters with its prickly vines. Eaten together, beans and corn provide complementary protein for humans.

You'll also see a "Three Sisters" garden. What we now call "companion planting"--using plants that grow better together than apart--seems to have been universally known among Native peoples. The "sisters" are corn, beans, and squash. Beans provide nitrogen for the corn and squash; the corn provides a support for the beans; and the squash (when it thrives, which it has so far failed to do in our garden this year) crowds out weeds, shades the ground to conserve moisture, and deters critters with its prickly vines. Eaten together, beans and corn provide complementary protein for humans.

Dagwaagin -- Fall Sometime around October, the wild rice will be ready for harvest. Then the Ojibwe women, who were the architects and home-builders in the community, would take down the birchbark panels of the wigwams, roll the birchbark up, and, leaving the pole framework behind, carry them along as the community moved to the smaller, inland lakes where the wild rice grows.

We put birchbark panels on one of the wigwams as part of our training, which gave us quite an appreciation of that particular bit of "women's work." (The one with the ponytail is me.)

Truly wild rice (as opposed to cultivated hybrids) is still harvested the traditional way, using knocking sticks like those pictured below. (Pro tip: If you're explaining this to visitors, be sure to call them knocking sticks, not knockers.) You can read about how wild rice is harvested in this article.

Biboon -- Winter The community dispersed for the winter in order to find enough game to support them. Trapping was also important, because pelts are thickest in winter.

Ziigwan -- Spring When the sap began to run, it was time for one more move: to the sugar bush for maple sugaring. Before the advent of European trade goods, the Ojibwe used wooden spiles to tap the trees and caught and boiled (!) the sap in birchbark containers. You can imagine that metal kettles made the process a good deal easier! If you're interested in reading more about maple sugaring then and now, you may enjoy this article.

In the Nisawa'ogaan

The long lodge in the Ojibwe village is furnished to house an imaginary three-generation family. Because they're imaginary, they don't mind if people handle all their belongings, so we invite visitors to touch whatever they like, feel the different furs, sit down, lie down, take a nap . . .

Next Time . . .

In our next post, Steve will give you a tour of the Canoe Warehouse. Just follow the path, and you'll be there. Before you go, take time for a game of lacrosse or to try your hand at constructing a mini wigwam.

*A word about names. Ojibwe (also Ojibway or Ojibwa) and Chippewa are transcriptions of the name that Europeans gave to the tribe. At the park, we use Ojibwe. The sign for the reservation says Chippewa, because that is the name used in US treaties. None of the above, not surprisingly, are what the people called themselves; that name is Anishinaabe, meaning "the original people."